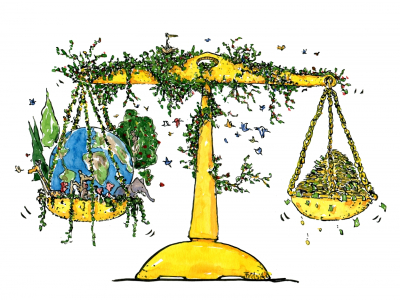

Natural Capital: Putting a Price tag on Nature

Does monetising nature make us more aware of its true value, or does it devalue it?

The COVID-19 crisis is a caveat that we need to change our ways in order to achieve a “carbon-neutral, ‘nature-positive’ economy”. When we went into quarantine, the pandemic awakened people’s inherent sense of biophilia as we appreciated parks as breathing spaces and sought to balance our isolation with connection to mother nature. For some businesses and ports, it has provided a hiatus, an opportunity to decarbonise and build a greener supply chain. As we begin our road to post-pandemic recovery, the value of ecology is now more than ever, being highlighted economically.

Natural capital has found its way into policymaking and business. There is no denying that climate change is a multi-billion-dollar industry, with futures in decarbonisation, carbon sequestration, carbon footprint, carbon trading, etc (and the list of carbon-related keywords goes on…) This has provoked debate amongst those who support the idea of quantifying nature through ecosystem services, and those who oppose the reduction of nature to numbers, in fear of turning nature from a free public good to a privatised commodity. A report released by the World Economic Forum observed that S$55.3 trillion dollars of economic value generated is moderately to highly dependent on nature. This includes factors like water, climate and pollination which largely affect the agriculture sector.

In landscape architecture, moulding nature has always come from a place where it should be used for the good of people and biodiversity. Ecosystem services are seen as a way to raise awareness, hold businesses accountable and convince decision-makers that nature is worth it as both a tangible and an intangible investment. Olmstead’s Central Park summarised as “Democracy made visible” during a time of sharp juxtaposition between the rich and poor, is still a very much relevant concept for open spaces today, but arguably, nature must also be made economically visible so that it will not be taken for granted or disregarded in planning.

Today, with climate change looming over our heads, placing an economic value on nature in turn protects it. Valuing ecosystem services also prompts companies to use more biodiversity-friendly solutions to fix pressing climate change issues. For instance, restoring wetlands to act as effective flooding mechanisms, ultimately saves on potential damage costs. Nature-based solutions such as bioswales, incorporating trees and parks onto our streets, and passive environmental design features help restore biodiversity, lower UHI and improve air quality- overall, increasing territorial resilience and property value.

As a response to the unprecedented global humanitarian and health crisis, it is unsurprising that more eco-ventures (Cleantech, Greentech etc) are being developed. Even though there is an endless pursuit of data and knowledge when it comes to nature, the financial vocabulary that connects ecosystem services to the economic system is becoming more defined. Stoffberg, in 2016, has pointed out in his research paper that we should engage in this opportune carbon industry in our landscape architecture practices by measuring and monitoring the carbon quantities in projects. The carbon stocks measured can then be used for carbon trading from the design studio, to construction and on to landscape maintenance. Ideally, by translating biodiversity values to economists in a language they can understand, and structuring a comprehensive ecosystems services framework, nature can be protected further and harnessed as an asset for the benefit of all.

About the Author

| Crystal is an aspiring landscape architect and urban designer at the National University of Singapore. She is passionate about designing cities for high levels of liveability and understanding how cities interact with their environment at the macro and micro scale. In an ideal world, Crystal believes that all systems should be concerned with achieving a sustainable balance and resilient design in the face of climate change. |